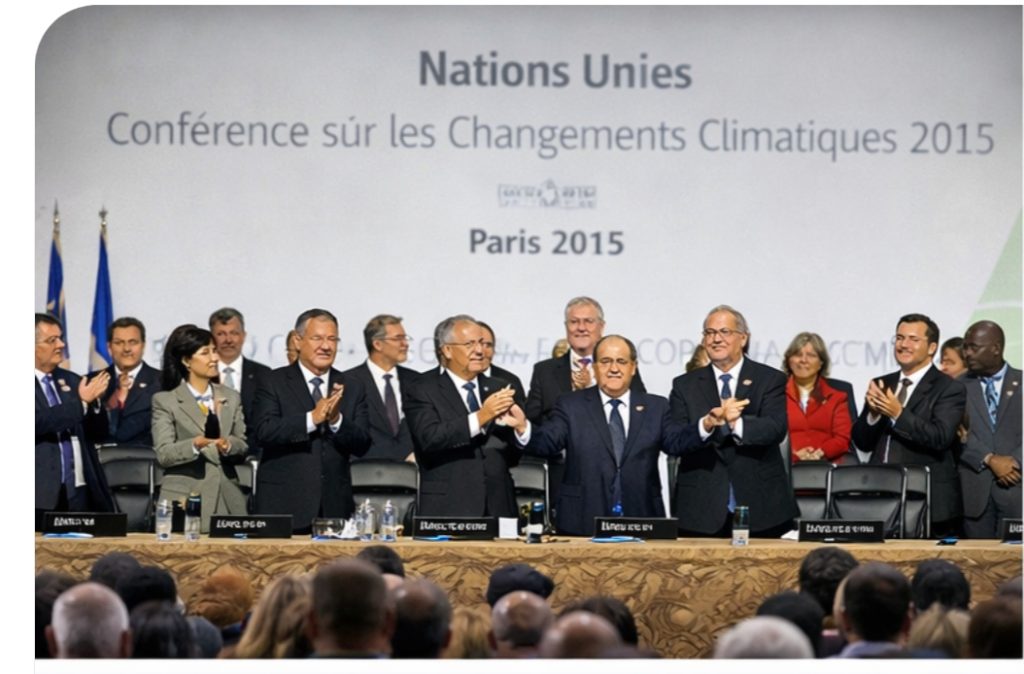

The United States’ decision to once again withdraw from the Paris Agreement has injected fresh uncertainty into global climate governance. The accord, adopted by nearly every country on Earth, was designed to limit global temperature rise to well below two degrees Celsius while mobilizing trillions of dollars in climate finance for vulnerable nations. With Washington stepping away, attention is now turning to whether international momentum on climate action can be sustained—and who will step forward to lead.

To understand the significance, imagine a grand negotiating hall. Around a vast table sit representatives from almost every nation—heads of state, diplomats, scientists, and civil society leaders—bound by a shared commitment to confront climate change. According to UN data, the Paris Agreement was adopted by 194 countries plus the European Union, making it one of the most widely supported international agreements in history.

At the head of this table are the world’s major contributors to global climate finance. The United Kingdom has pledged roughly $5.1 billion to the Green Climate Fund, followed closely by Germany at $4.9 billion, France at $4.6 billion, Japan at $4.2 billion, and Sweden at $2.2 billion. The United States once stood among them, with a pledged $3 billion contribution under the Obama administration.

Today, that seat is empty. Much of the U.S. pledge to the Green Climate Fund was never delivered, and the commitment was formally rolled back during the Trump administration’s first withdrawal from the Paris Agreement. This latest exit, which takes effect this week, marks an even deeper disengagement from global climate efforts.

According to Professor Zhang Xiliang of Tsinghua University, the implications go beyond symbolism. He argues that the U.S. has not only exited the Paris Agreement but has effectively distanced itself from the broader UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. As the world’s second-largest annual emitter and the largest historical emitter of greenhouse gases, Washington’s retreat leaves a significant gap in global leadership and accountability.

As the U.S. pulls back, China’s role at the climate table becomes more prominent. Beijing is not positioning itself as a traditional donor in the Western sense, but as a central climate actor with growing influence over implementation, technology, and rule-making. This shift reflects a broader rebalancing of climate governance.

Professor Zhang points to Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, which focuses on international cooperation through carbon markets and technology sharing. He notes that China is well placed to help shape standards, methodologies, and digital infrastructure for future global carbon credit systems. From emissions trading to clean-energy deployment, China’s technical capacity gives it room to play a more assertive role.

If global climate negotiators were once again gathered around that imaginary table, the empty U.S. chair would be impossible to ignore. But it could also serve as a catalyst. Countries across Europe, East Asia, and the Global South may feel compelled to reaffirm that climate action is not merely about signing agreements—it is about delivering finance, sharing technology, and rebuilding trust with communities already facing the harsh realities of a warming planet.