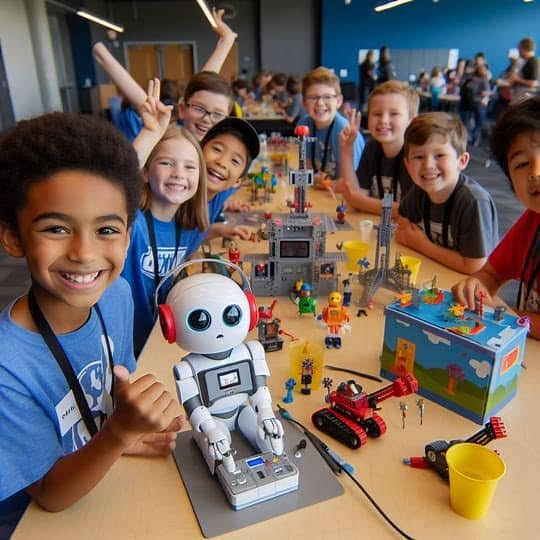

In an elementary school classroom tucked inside Beijing’s university district, 11-year-old Li Zichen confidently demonstrates a small robot he helped build. The device is simple: a remote-controlled vehicle that lifts and moves blocks, programmable through basic artificial intelligence. But for Zichen, the project opens the door to far bigger ideas—ideas that stretch all the way to Mars and the Moon.

He explains that when Chinese rovers encounter unexpected obstacles in space, like craters, they can’t wait for instructions from Earth. The delay in communication is too long. “The rover must decide on its own,” he says. That, to him, is why artificial intelligence is essential for China’s future in deep-space exploration.

Across the room, Zichen’s classmate Song Haoyue is using AI in a very different way. Instead of robots, she’s working on visual design. For a school competition, she used Wukong, an AI image-generation tool, to create a poster based on a Chinese myth about a bird that tries to fill the ocean with pebbles—an ancient story about perseverance and resilience.

While debates over AI in schools continue in the United States—ranging from fears about cognitive dependency to concerns over widening inequality—China has taken a decisive position. AI, here, is not optional. It’s policy.

Wang Le, the students’ computer science teacher at the Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications Affiliated Primary School, says the Ministry of Education has introduced a new national framework. Under it, AI must be integrated directly into the information technology curriculum. Starting this fall, all elementary and middle school students in Beijing—and several other regions—began formal AI education.

The structure is deliberate. Third graders learn foundational concepts. Fourth graders move into data and coding. By fifth grade, students are introduced to algorithms and “intelligent agents.” The goal, Wang explains, is not just education—but preparation. Preparation for life, work, and competition in a future shaped by intelligent machines.

This vision is closely tied to a broader national ambition summed up in a familiar slogan: Keji xingguo—“Build a strong nation through science and technology.” For China’s leadership, AI is not just a tool for innovation, but a pillar of national security and economic independence. The government has made it clear: China intends to be a global AI leader within the next few years.

Parents, however, view AI through a more personal lens. In a small apartment on the sixth floor of a walk-up building, Zichen’s father, Li Yutian, voices strong support for his son’s interest in robotics. He recently took Zichen to a Xiaomi factory to see automation at work firsthand. On the ride home, he offered practical advice: the future belongs to those who can work with AI, not compete against it.

Around dinner tables across China, families wrestle with the same questions facing parents elsewhere: Will AI make children overly dependent? Will it weaken creativity and problem-solving? Some believe strict internet controls can reduce the risks. Others, like Li Yutian, see a greater danger in avoidance. “Not embracing it,” he says, “may be the biggest risk of all.”

Song Haoyue’s father agrees—cautiously. He believes AI exposure must be age-appropriate, but supports making it a core subject. The future, he says, is uncertain. But inspiration, if introduced early, may help children find their place in a rapidly changing, AI-driven world.