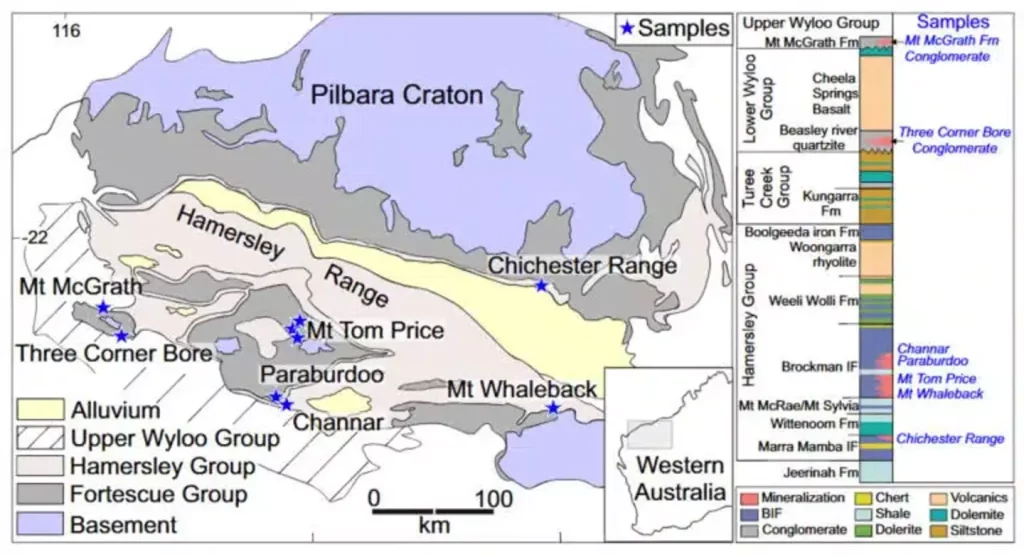

Australia may have just unearthed one of the most economically and scientifically significant discoveries of the modern era. Deep beneath the remote Hamersley region of Western Australia, researchers have identified what is now believed to be the largest iron ore deposit ever recorded—an estimated 55 billion metric tonnes of high-grade ore, valued at roughly £4.5 trillion ($6 trillion).

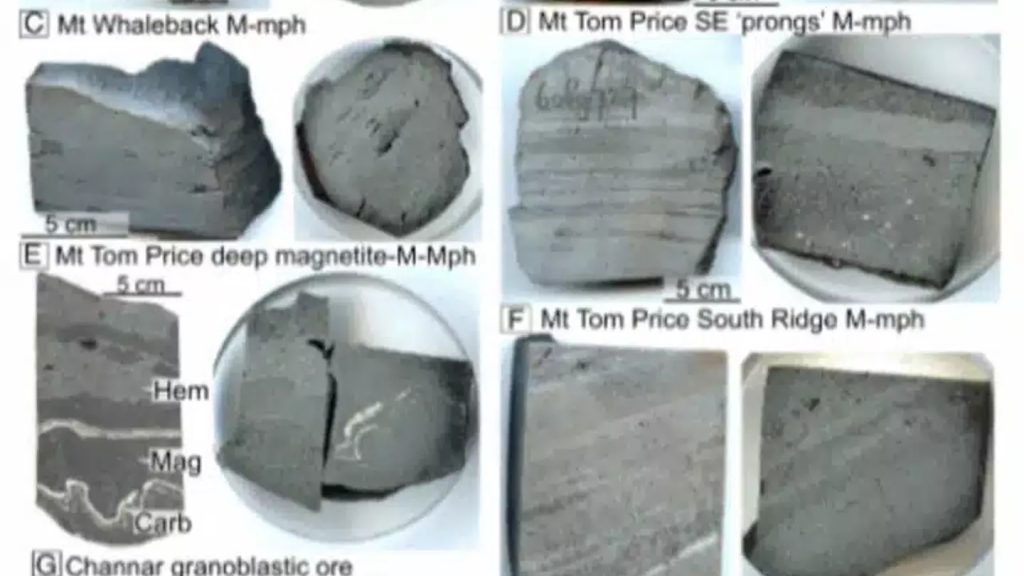

The scale alone is staggering. With iron concentrations exceeding 60 per cent, this deposit far surpasses earlier estimates that placed similar formations closer to 30 per cent purity. For a country that already dominates global iron ore exports, the discovery strengthens Australia’s position as the backbone of the world’s steel supply for decades to come.

Beyond the immediate economic implications, the find is forcing scientists to rethink long-held assumptions about how Earth’s crust evolved. The deposit, hidden in plain sight within a region mined for generations, reveals that even well-studied geological provinces can still hold transformative secrets.

What makes the discovery particularly remarkable is how it was found. Using advanced chemical and isotopic imaging techniques, scientists were able to reassess the age and composition of the Hamersley formations. Previous models dated the iron-rich layers to around 2.2 billion years old. New analysis now places their formation closer to 1.4 billion years, dramatically revising the geological timeline.

The research was led by Curtin University scientists and published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. According to Associate Professor Martin Danisík, a geochronologist on the project, the breakthrough lies in linking these massive iron deposits to ancient supercontinent cycles—periods when Earth’s landmasses collided, shifted, and reassembled.

“Finding a connection between these enormous iron deposits and shifts in supercontinent cycles gives us new insight into ancient geological processes,” Danisík explained. These tectonic upheavals likely created the precise conditions needed for iron to concentrate on such an unprecedented scale.

The implications extend well beyond academic geology. By directly dating iron oxide minerals using uranium–lead isotope analysis, the team established when and how the ore transitioned from relatively low-grade material into today’s ultra-rich deposits. This solves a long-standing mystery that had limited understanding of how the world’s largest banded iron formations evolved.

Dr Courtney-Davis, another member of the research team, emphasized that the discovery is as much about the future as it is about the past. “These technologies could make mining cleaner, less wasteful, and more environmentally responsible,” she said, pointing to the potential for more precise extraction methods that reduce waste and environmental impact.

For the global economy, the ripple effects could be profound. A vastly expanded long-term supply of high-grade iron ore may influence global iron prices, reshape steel production costs, and alter trade relationships, particularly with major importers such as China. While the deposit does not instantly translate into extractable wealth, it gives Australia an extraordinary strategic advantage in future resource planning.

Danisík has previously noted that understanding the timing of these deposits is key to understanding Earth itself. The collision and separation of ancient landmasses not only reshaped continents but also drove the chemical processes that concentrated iron into mineable form. “The shifting and collision of landmasses millions of years ago likely created the conditions for these vast accumulations,” he said.

In many ways, the discovery underscores a humbling truth: even in an era of satellites, AI modelling, and advanced geochemistry, the planet still holds secrets capable of reshaping science, industry, and global markets. Australia’s £4.5 trillion iron find is not just a mining story—it is a reminder that Earth’s deep history continues to shape humanity’s economic future.